Do You See the Lake?

On turning thirty and remembering what it is to believe in magic and mystery.

Every science textbook I’ve ever read1 has insisted Newton developed three basic laws of motion, but now that I’m thirty and have had some time to mull it over, I know for a fact he must not have had children when he wrote these.

It is my understanding that there are, in fact, four laws of motion, and the fourth one is called the Law of Ill-Timed Queries From Children in the Backseat.

The law is defined as follows: Children at rest in the backseat of the van will remain at rest in the backseat of the van until the precise moment when their mother begins actively merging onto the freeway during a heavy downpour, pushing 70, trying to squeeze in-between a semi-truck and a school bus, with Hakuna Matata blaring from the speakers, at which point they will be acted upon by an outside force and unleash their most jarring, existential questions.2

Last week, for example—as our minivan hurtled down the highway—my oldest wanted to know about America’s history of slavery and why do people have different skin colors and by the way, what is racism?

(She’s five).

This past weekend, she asked about Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and the 2024 presidential election.

(She’s five).

So far this week, she has asked the following:

Why is the man on the corner holding a cardboard sign that says, “Help”?

Why do people have to die?

Why does it take so long for the world to get un-broken?

(She’s five).

Listen, I read probably three dozen parenting books when this kid was not yet walking, and none of them told me that this is the typical progression:

Infant to baby.

Baby to toddler.

Toddler to preschooler.

Preschooler to fully-cognizant-child-who-asks-obliterating-questions-from-the-backseat-of-the-car.

None of the books told me that I would miss my exit—regularly.

None of the books told me how it would feel to hand back more questions than answers.

Here is how it will happen:

Around age five, your child will begin to understand that the world is much, much bigger than the four walls of your home.

Your child will hand you questions like the trinkets they drop into your palm—a gray pebble, a pinecone the size of your pinky nail, a green crayon with the paper peeled clean off.

Before answering, you will lock eyes with your child for one long, still beat.

You will suck in your breath. You will swallow hard.

You will try hard to make the world make sense—the joys and tragedies and mundanities—all your words tumbling over each other, tangled and knotted.

You will wonder how much longer until your child stops turning towards you like you are some sort of preeminent being. How much longer until they understand that, like them, you are only a person?

That, like them, you have spent most of your years trying to know the unknowable?

Like them, you have spent most of your time hurtling down the highway of your life asking, Why, why, why?

One afternoon, as my five-year-old and I chop vegetables at the counter, she asks me about stars.

Where do the stars go during the day?

I instinctively look out the window, past the fence hemming in our yard, past the towering pine tree across the street, and up into the clear, blue sky.

In this moment, she and I are the same—both of us slipping translucent half-moons of cucumber into our mouths. Both of us wondering the same thing.

How to see when we can’t see.

I do not know much about astronomy, but I do know this:

Some bright spots are invisible.

Some light you just have to trust is there.

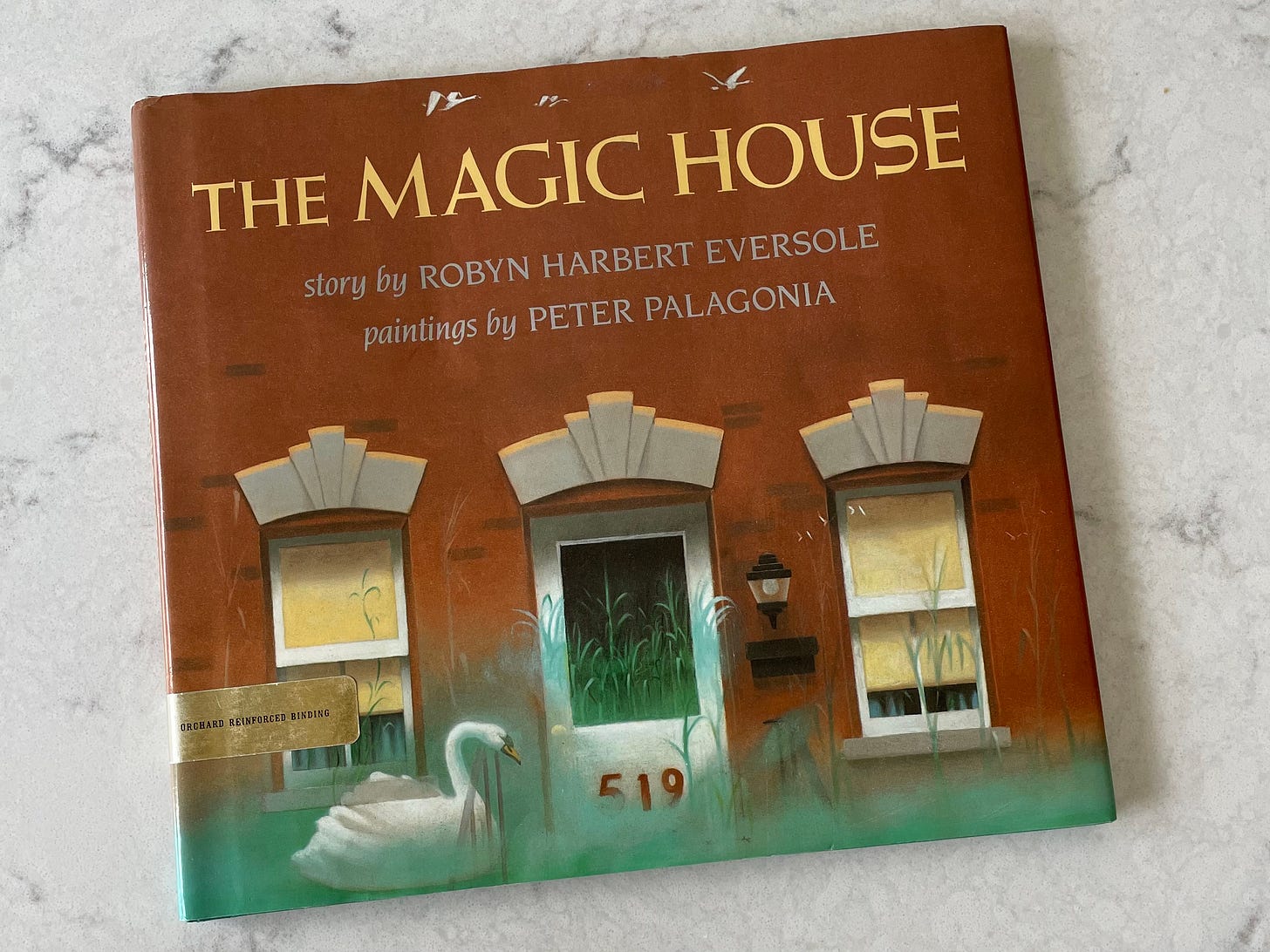

I remember exactly three things about my great-grandmother Mimi’s house: the stained glass sidelight window my great-grandfather built by hand, the boxes of Smacks cereal she kept in her brown kitchen cupboards, and my favorite picture book, The Magic House.

As a four-year-old, there was something about that picture book I found enchanting. Every time Mimi cracked open the cover, I was instantly transported to a world that was exactly like mine, while also not like mine at all.

The story begins with a young girl named April, who believes her house is magic. The basement, for example, is a cave with a friendly washing-machine monster. The living room is a desert with saguaro cactuses. The staircase is a cascading waterfall. The front hall is a rippling, blue lake.

April’s older sister, Meredith, tells April she is being ridiculous.

There is nothing magic about this house, she says.

The stairs are just stairs. A house is just a house.

When Meredith struggles while rehearsing for her upcoming ballet recital, April encourages her to practice in the front hall of the house—that is, the blue lake at the bottom of the waterfall.

Meredith acquiesces and, as she dances, she begins to glide and float. Her arms become wings. Her body transforms into the swan she is supposed to embody.

"Do you see the lake?” April asks her. “Do you see it?”

In this moment, Meredith realizes there really is more to the house than she originally believed.

Yes. There is some magic here.

Yes. She can see the lake.

The week before I turn thirty, I pull out The Magic House and read it to my five-year-old before she drifts off to sleep.

I kiss her forehead and carry the book downstairs to read it to myself a second time, alone on the couch, the room lit by a single lamp.

If my life is a story, then this is the part where I learn I had it backwards.

This is the part where I learn that growing up is less about building a tower of mounting certainties, and more about remembering what it is to believe in magic, in mystery.

If my life is a story, then I am here, folding down the corner of this page. Creasing it with my thumbnail. Underlining, underlining.

Trying to remember. Trying to make sure I can return to this page as many times as I need.

The evening of my thirtieth birthday, my husband carries a chocolate birthday cake to the table, three pastel candles twisted into its center, flickering.

The children’s voices rise around the table and my husband joins in, always and ever slightly off-key.

I think about the last years of my twenties—all the time I’ve spent trying to fold and tuck questions neatly into envelopes and file them away.

I think about how I used to be April, and somehow grew up to be Meredith.

The stairs are just stairs. A house is just a house.

There is nothing magic about the world.

This birthday feels different. I am less certain than I’ve ever been about most things, but it feels less like a dull ache and more like spaciousness.

More like swan wings. More like dancing in the face of all I do not know.

More like admitting that I do see the lake, after all.

The children finish singing, and for one brief moment, this makes sense: that I would celebrate growing up by remembering what it is to be a child. That I would bring in another year by pausing, by closing my eyes, by believing there is more to the world than my eyes can see before blowing out the flame.

The children are clapping now, a thin line of smoke rising from the wick, and my husband cuts the cake into thick slices.

“What did you wish for?” he will ask me later.

“More magic,” I will say.

“More mystery.”

And by this I mean: not many.

When my children turn sixteen, just to make sure they are really ready to drive in any and all conditions, you better believe I will be sitting in the passenger seat yelling deep, philosophical questions at them as they merge onto the freeway. WHAT HAPPENS WHEN WE DIE? WHAT IS IT THAT MAKES US HUMAN? ARE HOT DOGS ACTUALLY SANDWICHES? Don’t say I never did anything for my children.

I’m late to reading this, but I’m so glad I did. Your *words* are magic, friend. And I fully relate to the stress of having to merge while also answering what feels like impossible questions. We all have them, and apparently, they can begin all the way back at 5.

okay, well, you've done it again <3 I just love your words so much, Krista. This was just beautiful.